There are some scenarios where the order matters Link to heading

Let’s say that you have an api that can receive “actions” to be performed on a given endpoint.

Think about you buying something on Amazon and then changing your mind and revoking your order. You don’t want those two actions to be swapped, otherwise the cancellation will be refused (the order you want to cancel do not exists yet) and then the item you don’t want anymore will be ordered (since the action of ordering the item receives the backend after the cancelation).

Also, in this (not so) hypothetic scenario, processing each message has a cost. For example, the message needs to be validated against some external endpoint, or it needs to be enriched with data that can be found on a database.

So here we have a dilemma: we would like to take advantage of go concurrency system and increase the throughput by processing the messages concurrently, but at the same time the order matters and you can’t just pass the events to the goroutines because the order the messages are received won’t be respected.

Processing the messages in a concurrent fashion would amortise the processing cost of each message. By processing the messages sequentially, a queued message will have to wait all the messages received before.

So my question is, can we take advantage of the Go powerful concurrency support for this inherently sequential problem? Link to heading

And is it hard?

All this to say that I wanted to write a simple example that reorders the messages as soon as they are processed concurrently.

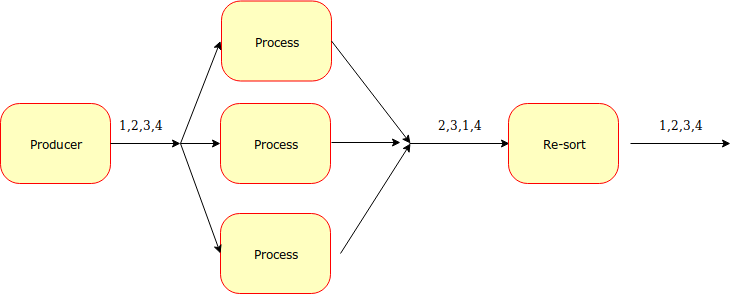

The basic idea is to mark each message with a sequence number, handle many messages concurrently, and pass the results to another goroutine that will then reorder the.

The architecture is something like this:

I tried to simulate the time consuming operation with a random interval between 1 - 100 milliseconds:

howLong := rand.Intn(100)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(howLong) * time.Millisecond)

The consuming part only involves printing the result of the computation on the standard output, in order to be able to check if the re-ordering was done properly.

Channels and goroutines Link to heading

The moving parts are:

- a producer goroutine that writes on a source channel

- many worker goroutines that process the messages sent on the source channel & write on the same output channel

- a result processor goroutine that reads the results from the output channel, try to reorder them and then print the output

The whole project can be found here

The results Link to heading

Non concurrent:

go run . 0,37s user 0,31s system 1% cpu 49,069 total

Concurrent:

go run . 0,33s user 0,17s system 66% cpu 0,745 total

The take home lesson Link to heading

This working example demonstrates how the communicating paradigm makes it easy to handle and manipulate events concurrently with Go. The fact that we do have requirements of sequentiality does not mean that we can’t try to exploit all the cores available in order to take advantage of the multiprocessing powers of Go.

Where to go from here Link to heading

During the first implementation, I kept the “reordering part” as simple as I could, meaning that the events are just appended to a slice, then the result processor keeps a “last processed” sequence number and tries to retrieve the next event to be emitted.

The code for the “draining part” is:

func drainParked(parked *[]result, next *int) {

for {

var found bool

for i, val := range *parked {

if val.seqNum == *next {

fmt.Printf("Processed %d\n", val.seqNum)

*next++

*parked = append((*parked)[:i], (*parked)[i+1:]...)

found = true

break

}

}

if !found {

return

}

}

}

This code is definitely not optimized, we could leverage the profiling tools provided by Go in order to see how to optimize it.

Fallacies Link to heading

The alignement assumes that the concurrent calls will take (almost) the same amount of time and that they will eventually end.

A non terminating goroutine would result in blocking the entire flow: a smarter (and production ready) implementation should take timeouts into account.