Even when knowing Go, writing a Kubernetes controller is intimidating.

In this post, I’ll introduce the Kubernetes operating model, how objects are mapped and what are the tools provided by the go-client framework to write bullet proof controllers. In a following post I will explain how to put all the pieces together and how to define and consume custom types.

I will describe the core components like:

- ClientSets

- Informers

- Work Queues (and RateLimiting Work Queues)

and how they fit together in writing a Kubernetes controller.

The content of this post is inspired by the “It’s all about reconciliation, anatomy of a kubernetes controller” talk I gave this summer as part of the GoWay conference.

The slides are available here:

The Kubernetes Model Link to heading

The kubernetes model is declarative and not imperative. This means that instead of asking a kubernetes cluster to execute actions, we declare the state we want it to be in, and we wait for it to reconcile our request and to reach that state.

In the following (abused) example of ReplicaSet, we ask the cluster to deploy 3 replicas of a given pod:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: ReplicaSet

metadata:

name: frontend

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

tier: frontend

template:

metadata:

labels:

tier: frontend

spec:

containers:

- name: php-redis

image: gcr.io/google_samples/gb-frontend:v3

When we change our mind, and we set the number of replicas to 2, we are not sending a command to the cluster asking to remove a pod, we are declaring the new state we want the cluster to be in. This makes a substantial difference and is the key in understanding how Kubernetes works.

The representation of the state is stored in a key-value storage shared among all the components that make a Kubernetes cluster. Those components in charge of reading the desired state and reconciling it are commonly referred to as controllers.

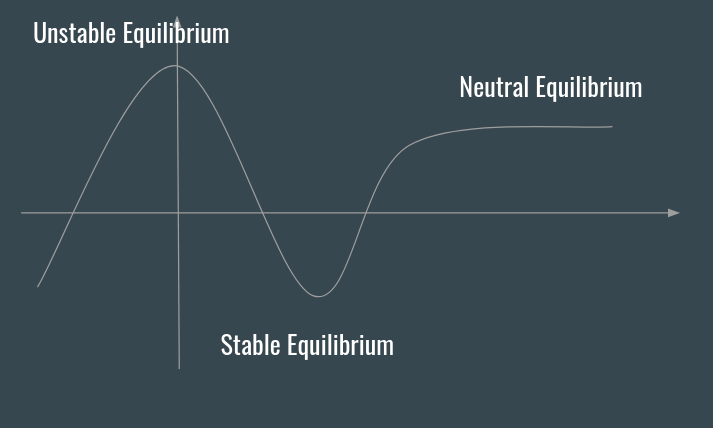

For this reason, a cluster can be seen as a dynamic system, where the equilibrium is disturbed by event, that can be handled by controllers, generating other events handled by other controllers, up to a new state of equilibrium (this is probably also one of the few chances where I can use a graph :P).

Complications Link to heading

Race conditions Link to heading

As a consequence of having several (distributed) components interacting with the storage (commonly implemented using etcd), two different controllers may write the same data.

The way Kubernetes handles it is via optimistic concurrency, which basically means “the first writer wins, the second gets an error”, which is different from the locking mechanisms we are used to in “regular” databases.

It also means that the overhead of handling the error and possibly retrying is pushed back to us, writing those controllers.

(Note that this works because the number of writes is way less than the number of reads).

Missed events Link to heading

This is the norm, for many reasons.

- Pods can die (or get rescheduled)

- The network is not reliable

- Nodes can die

Level Driven vs Edge Driven Link to heading

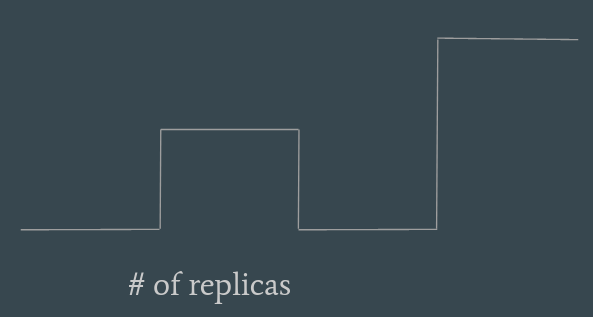

There are two ways to handle events. Let’s consider the example of the variations of a replica set.

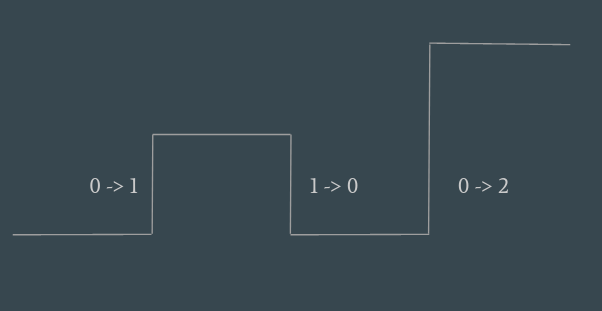

The terminology comes from electronics. You can listen to changes happening at the edges, considering the variation of the number of pods, going from 1 to 0 for example, or you can listen to the level, the value that is constantly requested at any given point in time.

Edge Driven Link to heading

When listening to the variations happening on the edges, the behaviour is driven by the variation of the data observed at the edges.

Apparently, this is easier to implement. When the number of replicas grows by one, we simply spin up a new pod. But is this equally robust?

What happens if the controller implementing this behaviour gets killed before handling the 1 -> 0 variation? We would end up creating 3 pods, while the user requested for 2.

Level Driven Link to heading

With level driven, we constantly monitor the level, reconciling the desired number of pods with the one expressed by the level.

This requires more logic, but it is definitely more robust. The controller needs to observe not only the requested value, but also the state of the cluster, and react accordingly.

It’s like constantly polling the requested state and the actual state, and applying an idempotent logic.

Edge Triggered, level driven Link to heading

This is the way to go. The waking points are the variations (or, the first variation in case our controller is just spinning up), but the logic is implemented only looking at the requested state. If we handle the current state but ignore the old one, we can afford missing events.

Writing a controller in Go Link to heading

There is no black magic, and the controller working principle is pretty simple: read / write data to the key value store, and react accordingly.

You deal with types Link to heading

A kubernetes type is identified by it’s rest url:

/apis/batch/v1/namespaces/FOO/jobs

The path segments represent the various components of a type:

- Group

- Version

- Resource

The type of the object returned by the rest url is referred to as kind.

In kubernetes there are many kinds, related to different resources you handle when interacting with a Kubernetes cluster, such as pods, services, etc.

All kinds share common traits Link to heading

This below is the go struct for a Pod.

type Pod struct {

metav1.TypeMeta

metav1.ObjectMeta

Spec PodSpec

Status PodStatus

}

In the Kubernetes Go API there is an intensive use of struct embedding (one of my favourite features of Go).

All the objects embed TypeMeta and ObjectMeta.

type TypeMeta struct {

Kind string

APIVersion string

}

TypeMeta contains information related to the specific type.

type ObjectMeta struct {

Name string

GenerateName string

Namespace string

SelfLink string

UID types.UID

ResourceVersion string

Generation int64

.

.

ObjectMeta contains information that is common to all the objects handled by the Kubernetes API.

Spec and Status Link to heading

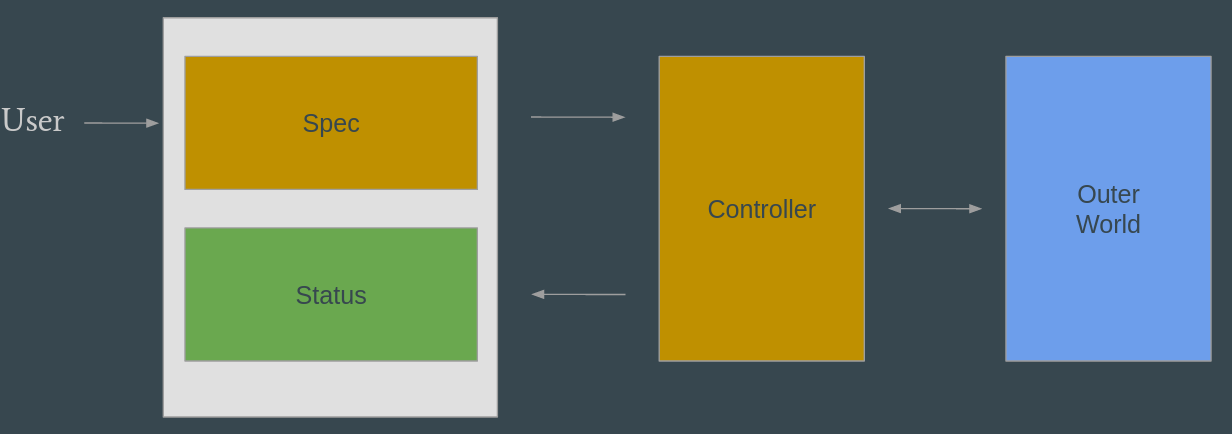

spec and status are a convention followed by all the kubernetes objects. They are type specific, and the idea behind them is pretty simple: spec represents the desired state set by the user, status represents the status observed by the controller and reported back to the user.

To Sum Up Link to heading

A controller job is to read what the user wants (the spec), apply it and report the status back.

Depending on the controller, applying the spec may result in changing specs of other types (such as the replicaset vs pods example) or interacting with something external to the cluster (such as the underlying baremetal configuration). Ideally, the spec is reconciled, the status reaches the desired one and is reported back to the user.

There’s no such thing as a “Go Client” Link to heading

When I approached kubernetes for the first time, I thought there was an universal go library to handle all the types.

The truth is, client-go is more like a framework: there is a client for each api group, for example:

- the client used to handle pods is the one related to the

coregroup - the client used to handle daemonsets is the one related to the

appgroup - the client used to handle networkpolicies is the one related to the

networkinggroup

All these clients are grouped together in a clientset.

How do we get a pod? Link to heading

The starting point is to retrieve the cluster configuration. One common way to do that is to read the kubeconfig file, but there are alternatives (especially if the controller runs inside a cluster).

config, _ := clientcmd.BuildConfigFromFlags("", "/home/fede/kubeconfig")

clientset, _ := kubernetes.NewForConfig(config)

Once we have the clientset, we can perform operations on collections of objects (such as List) or on specific instances (such as Get):

pods, _ := clientset.CoreV1().Pods("testnamespace").List(v1.ListOptions{})

ds, _ := clientset.AppsV1().DaemonSet("testnamespace").Get("myset", v1.GetOptions{})

The available verbs are the ones expected from a CRUD client: Get, Create, Delete, Update, List, Patch, Watch.

Watch is special Link to heading

The Watch method is the key for handling the event driven behaviour of our controllers.

Watch returns a Watcher interface, from where we can get a channel that gets notified of incoming events:

type Interface interface {

Stop()

ResultChan() <-chan Event

}

type Event struct {

Type EventType

Object runtime.Object

}

This is pretty low level, and the controller is left implementing the error handling mechanism, for example in case of lost connection with the apiserver.

Informers Link to heading

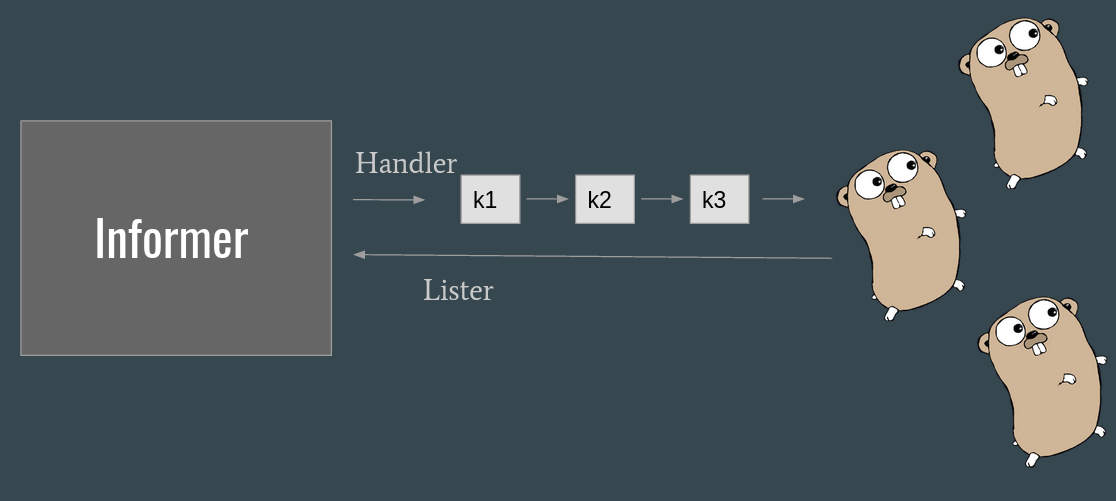

Informers are a higher level construct that relies on Watchers to implement the event handling.

They differ because:

- They implement a local cache of the data observed, that can be accessed via the

Listerinterface - They notify the consumer via a Handler

- They handle error situations such as reconnections

Shared Informers Link to heading

The specific type of informers that is recommended to use are SharedInformers.

The main difference is related to the impacts of the subscription on the api server. Even if multiple subscriptions are started (inside the same process), the SharedInformer makes sure that only one subscription is opened on the ApiServer, without adding extra overhead.

import kubeinformers "k8s.io/client-go/informers"

// create the informer

kubeInformerFactory := kubeinformers.NewSharedInformerFactory(kubeClient, time.Second*30)

podsInformer := kubeInformerFactory.Core().V1().Pods()

// register the listeners

podsInformer.Informer().AddEventHandler(cache.ResourceEventHandlerFuncs{

AddFunc: func(obj interface{}) {

},

...

})

// access the local cache

podsInformer.Informer().Lister().Pods("namespace").Get("podname")

The informers are type specific, and when reading the data through the Lister we are not hitting the remote endpoint, but relying on a local copy of the object, stored in the cache of the informer.

Note: The objects provided by the informer are owned by the informer. Since multiple clients may be registered against the same informer, modifying the object may have unpredictable results. Because of this, when needed it is common practice to create a local copy using the DeepCopy method available on those objects.

Work Queues Link to heading

Work queues are the final piece of the puzzle.

The go-client framework provides a priority queue that fits particularly well in the kubernetes patterns.

They allow multiple consumers for the same source of events, and decouple the callbacks (which are supposed to be quick) from the consumption of the events.

The interface of a work queue looks like:

type Interface interface {

Add(item interface{})

Len() int

Get() (item interface{}, shutdown bool)

Done(item interface{})

ShutDown()

ShuttingDown() bool

}

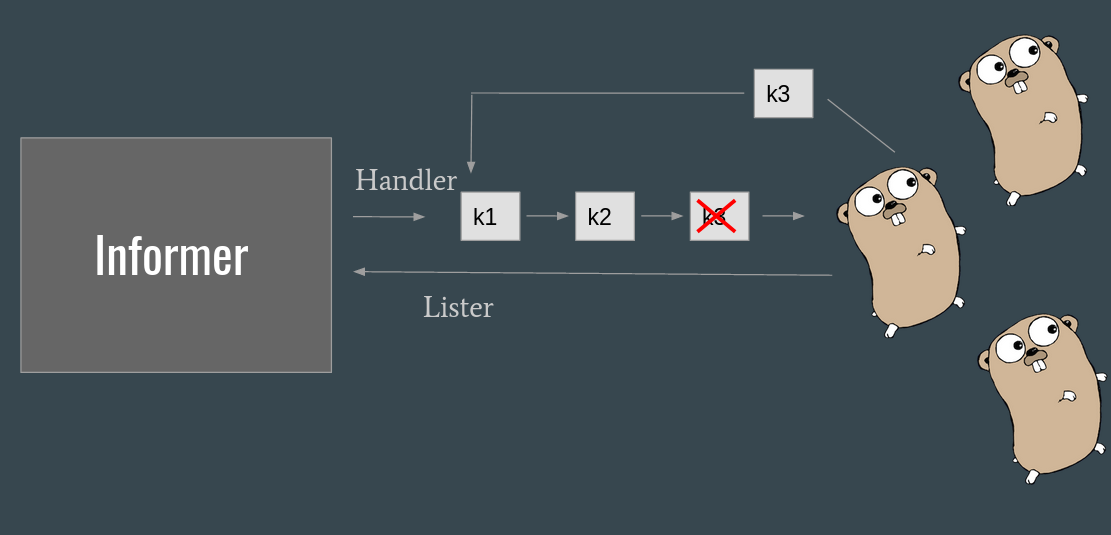

The safer and recommended way to use the queue is to put only the key of the event in the queue. On the other end of the queue the consumer can retrieve the last image from the informer’s cache, using the lister (remember, edge triggered but level driven?).

This means that all the variations of a given key are squashed until a consumer handles the key.

A positive side effect of this implementation is also that it is impossible to have two consumers handling events related to the same key at the same time (and thus, we can’t have deletion handled before creation, for example).

What if a new event is added when a consumer is consuming the same key?

This is the reason for having the Done method. The consumer is expected to mark the key as done when it finishes handling it, so the queue can re-submit the key.

Rate Limiting Work Queues Link to heading

A special type of queues is the rate limiting ones.

The main difference with WorkQueues, is the possibility of putting the event back to the queue in case a recoverable error happens.

The interface looks like

func NewRateLimitingQueue(rateLimiter RateLimiter) RateLimitingInterface

type RateLimitingInterface interface {

DelayingInterface

AddRateLimited(item interface{})

Forget(item interface{})

NumRequeues(item interface{}) int

}

As we already discussed, in this type of applications recoverable errors are normal (just think about the optimistic concurrency scenario). Having a well defined and robust way to perform retries is necessary.

With Rate Limiting work queues, the consumer can throw the event back to the queue calling AddRateLimited, and the queue will re-propose the item following the rate limiting logic implemented by the queue (default ones follow an exponential backoff mechanism).

The Forget method is how we notify the queue the item was processed successfully and it can stop sending it to the consumer.

Implementing this type of behaviour requires extra logic in place (idempotency among the others) to make sure the event is reconciled properly.

In the next post, I will cover how the code looks like, how we can implement the same mechanisms for user defined types, and how to use the non type-safe client.

If you liked this post, consider following me on twitter.