Disclaimer: Link to heading

In this post I am trying to cover a proper approach to a common problem. I am still in the process of wrapping my head around RxJava so what I write here might not be the best way to solve the problem.

Cached requests with RxJava Link to heading

Lately I’ve been trying to develop a rest backed app using RxJava. I must admit that once you get in the proper mental mood, RxJava almost feels like cheating. Everything looks cleaner, multiple requests can be composed and manipulated easily, the StrictMode gets satisfied by observing on the ui thread and subscribing on a different thread, and all the nice things that can be read about how cool is RxJava with Android. What I could not find easily, was how to store the result of a request and be sure that even in case of no network, a cached content was available for the user, while still handling everything in a reactive fashion.

Caching vs non caching Link to heading

Going straight from rest result to the UI is appropriate in many cases, for example when displaying the result of a search whose arguments are not predictable (think about Ebay, or Amazon where the user is looking for something different every time).

However, there are cases when the results fetched earlier are still significant and displaying them can improve the user experience significantly, compared to a spinning wheel or a white page. Those cases include your twitter feed, a local weather forecast that was fetched just 5 minutes before, or the list of the github repos of a given user.

Here you can see the difference between a non cached version and a cached version of the same activity:

For this reason I tried to figure out what could have been a clean way to cache the results of a request while keeping the flow in a reactive fashion.

The storage as the unique source of the truth Link to heading

All reactive Link to heading

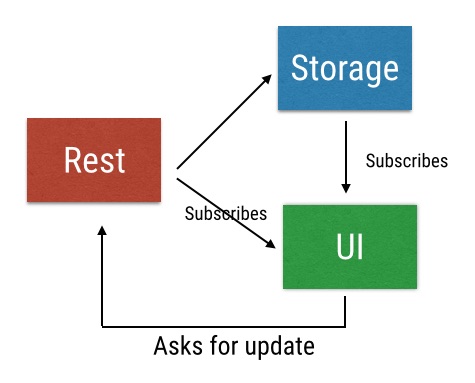

If we want to cache the data while keeping everything inside the same subscription, things get a bit messy. The result of the request is thrown at the UI and the response is also stored in the storage. The UI subscribes from the storage too but checks which result came first and if the data is too old.

Cached Link to heading

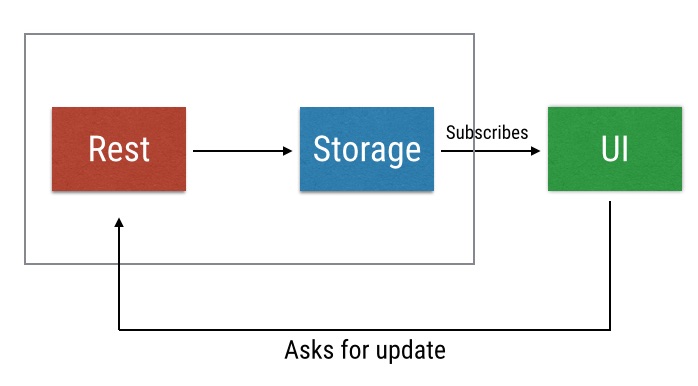

In this hybrid variant, the UI subscribes only to the storage, and a facade class wraps the storage and the subscription to the retrofit client that feeds the storage. Once the storage is filled with new data, the UI thread is automatically notified of every change.

In this scenario the observable acts as a hot observable, the first time it gets subscribed it emits the content of the storage, and any other change it might happen to it.

Talk is cheap, show me the code Link to heading

A working example of the following code can be found in my github repo here To write this sample, I started from the abused Github apis which seems to power the 99% of the rest related examples. Sorry about that.

First there is the storage. I wrapped a SQLite helper (which I happily generated with my handy script) with a class that contains a PublishSubject which can be subscribed to and which we will notify when the insertion methods are called:

public class ObservableRepoDb {

private PublishSubject<List<Repo>> mSubject = PublishSubject.create();

private RepoDbHelper mDbHelper;

private List<Repo> getAllReposFromDb() {

List<Repo> repos = new ArrayList<>();

// .. performs the query and fills the result

return repos;

}

public Observable<List<Repo>> getObservable() {

Observable<List<Repo>> firstTimeObservable =

Observable.fromCallable(this::getAllReposFromDb);

return firstTimeObservable.concatWith(mSubject);

}

public void insertRepo(Repo r) {

// ...

// performs the insertion on the SQLite helper

// ...

List<Repo> result = getAllReposFromDb();

mSubject.onNext(result);

}

}

What we have here is the first piece of the puzzle: a storage that can be subscribed to. The concatenation is needed because we want it to emit the content of the storage as soon as it gets subscribed.

Then there is the facade class, where we get the observable from and to which we start a new update:

public class ObservableGithubRepos {

ObservableRepoDb mDatabase;

private BehaviorSubject<String> mRestSubject;

// ...

public Observable<List<Repo>> getDbObservable() {

return mDatabase.getObservable();

}

public void updateRepo(String userName) {

Observable<List<Repo>> observable = mClient.getRepos(userName);

observable.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(Schedulers.io())

.subscribe(l -> mDatabase.insertRepoList(l));

}

}

Note that everything happens far from the UI thread. This is because we are going to subscribe to the database observable as the unique source of truth.

Now, given that the observable is now hot, we can’t listen for its onComplete in order to stop any progress indicators we might put in place. What we need is another subject that can be bound to the update request, so here it is the new facade class:

public class ObservableGithubRepos {

// ...

public Observable<List<Repo>> getDbObservable() {

return mDatabase.getObservable();

}

public Observable<String> updateRepo(String userName) {

BehaviorSubject<String> requestSubject = BehaviorSubject.create();

Observable<List<Repo>> observable = mClient.getRepos(userName);

observable.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(Schedulers.io())

.subscribe(l -> {

mDatabase.insertRepoList(l);

requestSubject.onNext(userName);},

e -> requestSubject.onError(e),

() -> requestSubject.onCompleted());

return requestSubject;

}

}

In the UI client (activity or fragment) we’ll need to subscribe to the storage in order to get the data and to the request observable in order to stop the progress indicators. An observable that emits the state of the pending request is returned every time an update is being requested.

mObservable = mRepo.getDbObservable();

mProgressObservable = mRepo.getProgressObservable()

mObservable.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread()).subscribe(l -> {

mAdapter.updateData(l);

});

Observable<List<Repo>> progressObservable = mRepo.updateRepo("fedepaol");

progressObservable.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(s -> {},

e -> { Log.d("RX", "There has been an error");

mSwipeLayout.setRefreshing(false);

},

() -> mSwipeLayout.setRefreshing(false));

Please remember that the DbObservable is a hot one, so every time a call to updateRepo happens, the db will be fed with the result of the query and the ui will get subsequently notified.

SqlBrite Link to heading

If all this wrapping seems too laboruous, the prolific guys from Square wrote SqlBrite which is a super generic database wrapper that was written for this same purpouse. I am sure it’s better and more battle field tested than the poor man’s version we can write by ourselves.

Conclusion Link to heading

I don’t know if this is an healthy way to use RxJava. Maybe I ended up with this scenario only because I am not 100% confident with RxJava and I am putting some non rx-ness in the middle to better control it. Here we need to choose where to place the operators, since we can modify the flow that feeds the storage from the http client, or the flow that comes out of the storage itself.

In any case, having an unique source of truth seems more clear, and I feel that in this way it would be a lot easier to do stuff like prefetching, scheduling updates so the user is presented with fresh data (remember having your app work like magic?), checking if an update is worth to be done at all (such as displaying a 5 minutes old weather forecast) and stuff like that.

Thanks to Fabio Collini for spotting a lot of mistakes in the first draft of this posts, and to Riccardo Ciovati for proof reading it.